Due to the lack of hygiene, the disease raced

through the port town. Rumors of a plague in the Orient had circulated in Europe since

1346. In an age given to hyperbole, everyone believed the news of 23 million people dying

to be exaggerated. Not until 1347 did Europe finally come to understand the terrible

accuracy of that figure.

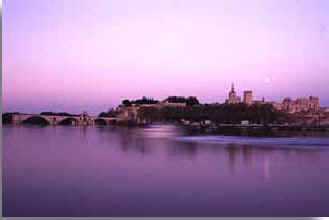

By January, 1348, the plague had infected other port towns, especially Marseille and

Tunis. In Europe it traveled up the Rhone river to call on the papal court at Avignon. It

quickly spread to Bordeaux, Lyon, and Paris, then to Burgundy, Normandy, and England. From

Sicily it traveled to Italy, Switzerland, and Hungary. Bohemia and Russia were largely

unaffected until 1351. The general course of the disease in a geographic area ran about

six months. It would then fade during winter, unless the area affected was densely

populated, to resume with renewed vigor the following spring.

Accurate mortality rates are difficult to find. The best estimates, based on a

conservative reading of the records, place the mortality rate at about one-third of

Europe's population. This would translate into about twenty million people dying between

1348 and 1350.

Approximately 50% of the citizens of Paris, 60% of Bremen and Hamburg, and 75% of

Florence, died in one year, their entire economic systems collapsing. In Venice, which kept excellent records, 60% died over the course of

18 months: 500-600 a day at the height.

Certain professions suffered higher mortality, especially those whose duties brought

them into contact with the sick--doctors and clergy. In Montpellier, only seven of 140

Dominican friars survived. In Perpignan, only one of nine physicians survived, and two of

18 barber-surgeons. The death rate at Avignon was 50% and was even higher among the

clergy. One-third of the cardinals died. Clement VI had to consecrate the Rhone river so

corpses could be sunk in it, for there was neither time nor room to bury them.

The dead outnumbered the living by such a margin that in some cities the bodies were

allowed to pile up outside in the streets, adding to the contagion. The more communal the

living quarters were, the more thoroughly the plague could do its task. This meant that

many convents and monasteries became extermination camps for their inhabitants. In some,

every person died. The "black death," as the plague was known, influenced

virtually every aspect of life in the latter part of the century.

The plague touched everyone, rich and poor alike. The noted Florentine historian,

Villani, wrote this: "And many lands and cities were made desolate. And the plague

lasted until......." Villani left a blank at the end of the sentence, planning to

fill in a date after the plague had abated. He never did. Villani died in 1348 from the

plague.

The whole community of scholars suffered as universities and schools, usually located

in regions hardest hit, were closed or even abandoned. Sixteen of the forty professors at

Cambridge died. Likewise in the institutions of the Church. The priests died and no one

could hear confession. Bishops died, and so did their successors and even their

successors.

The plague took its toll among the nobility: King Alfonso XI of Castile was the only

reigning monarch to die of the plague but many others, including the queens of Aragon and

France, and the son of the Byzantine emperor died. The effect at local levels was more

severe. City councils were ravaged and whole families of local nobles were wiped out.

Courts closed down and wills could not be probated.

Marchione di Coppo Stefani wrote his Florentine Chronicle in the late 1370s

Third Son

Third Son

Fourth

Son

Fourth

Son

Imola

Imola

Casal Fiumanense

Casal Fiumanense Castel del Rio

Castel del Rio

Castel Guelfo

Castel Guelfo Mordano

Mordano

Cesena

Cesena